My LLM coding workflow going into 2026

Best practices for staying in control while coding with AI

AI coding assistants became game-changers this year, but harnessing them effectively takes skill and structure. These tools dramatically increased what LLMs can do for real-world coding, and many developers (myself included) embraced them.

At Anthropic, for example, engineers adopted Claude Code so heavily that today ~90% of the code for Claude Code is written by Claude Code itself. Yet, using LLMs for programming is not a push-button magic experience - it’s “difficult and unintuitive” and getting great results requires learning new patterns. Critical thinking remains key. Over a year of projects, I’ve converged on a workflow similar to what many experienced devs are discovering: treat the LLM as a powerful pair programmer that requires clear direction, context and oversight rather than autonomous judgment.

In this article, I’ll share how I plan, code, and collaborate with AI going into 2026, distilling tips and best practices from my experience and the community’s collective learning. It’s a more disciplined “AI-assisted engineering” approach - leveraging AI aggressively while staying proudly accountable for the software produced.

If you’re interested in more on my workflow, see “The AI-Native Software Engineer”, otherwise let’s dive straight into some of the lessons I learned.

Start with a clear plan (specs before code)

Don’t just throw wishes at the LLM - begin by defining the problem and planning a solution.

One common mistake is diving straight into code generation with a vague prompt. In my workflow, and in many others’, the first step is brainstorming a detailed specification with the AI, then outlining a step-by-step plan, before writing any actual code. For a new project, I’ll describe the idea and ask the LLM to iteratively ask me questions until we’ve fleshed out requirements and edge cases. By the end, we compile this into a comprehensive spec.md - containing requirements, architecture decisions, data models, and even a testing strategy. This spec forms the foundation for development.

Next, I feed the spec into a reasoning-capable model and prompt it to generate a project plan: break the implementation into logical, bite-sized tasks or milestones. The AI essentially helps me do a mini “design doc” or project plan. I often iterate on this plan - editing and asking the AI to critique or refine it - until it’s coherent and complete. Only then do I proceed to coding. This upfront investment might feel slow, but it pays off enormously. As Les Orchard put it, it’s like doing a “waterfall in 15 minutes” - a rapid structured planning phase that makes the subsequent coding much smoother.

Having a clear spec and plan means when we unleash the codegen, both the human and the LLM know exactly what we’re building and why. In short, planning first forces you and the AI onto the same page and prevents wasted cycles. It’s a step many people are tempted to skip, but experienced LLM developers now treat a robust spec/plan as the cornerstone of the workflow.

Break work into small, iterative chunks

Scope management is everything - feed the LLM manageable tasks, not the whole codebase at once.

A crucial lesson I’ve learned is to avoid asking the AI for large, monolithic outputs. Instead, we break the project into iterative steps or tickets and tackle them one by one. This mirrors good software engineering practice, but it’s even more important with AI in the loop. LLMs do best when given focused prompts: implement one function, fix one bug, add one feature at a time. For example, after planning, I will prompt the codegen model: “Okay, let’s implement Step 1 from the plan”. We code that, test it, then move to Step 2, and so on. Each chunk is small enough that the AI can handle it within context and you can understand the code it produces.

This approach guards against the model going off the rails. If you ask for too much in one go, it’s likely to get confused or produce a “jumbled mess” that’s hard to untangle. Developers report that when they tried to have an LLM generate huge swaths of an app, they ended up with inconsistency and duplication - “like 10 devs worked on it without talking to each other,” one said. I’ve felt that pain; the fix is to stop, back up, and split the problem into smaller pieces. Each iteration, we carry forward the context of what’s been built and incrementally add to it. This also fits nicely with a test-driven development (TDD) approach - we can write or generate tests for each piece as we go (more on testing soon).

Several coding-agent tools now explicitly support this chunked workflow. For instance, I often generate a structured “prompt plan” file that contains a sequence of prompts for each task, so that tools like Cursor can execute them one by one. The key point is to avoid huge leaps. By iterating in small loops, we greatly reduce the chance of catastrophic errors and we can course-correct quickly. LLMs excel at quick, contained tasks - use that to your advantage.

Provide extensive context and guidance

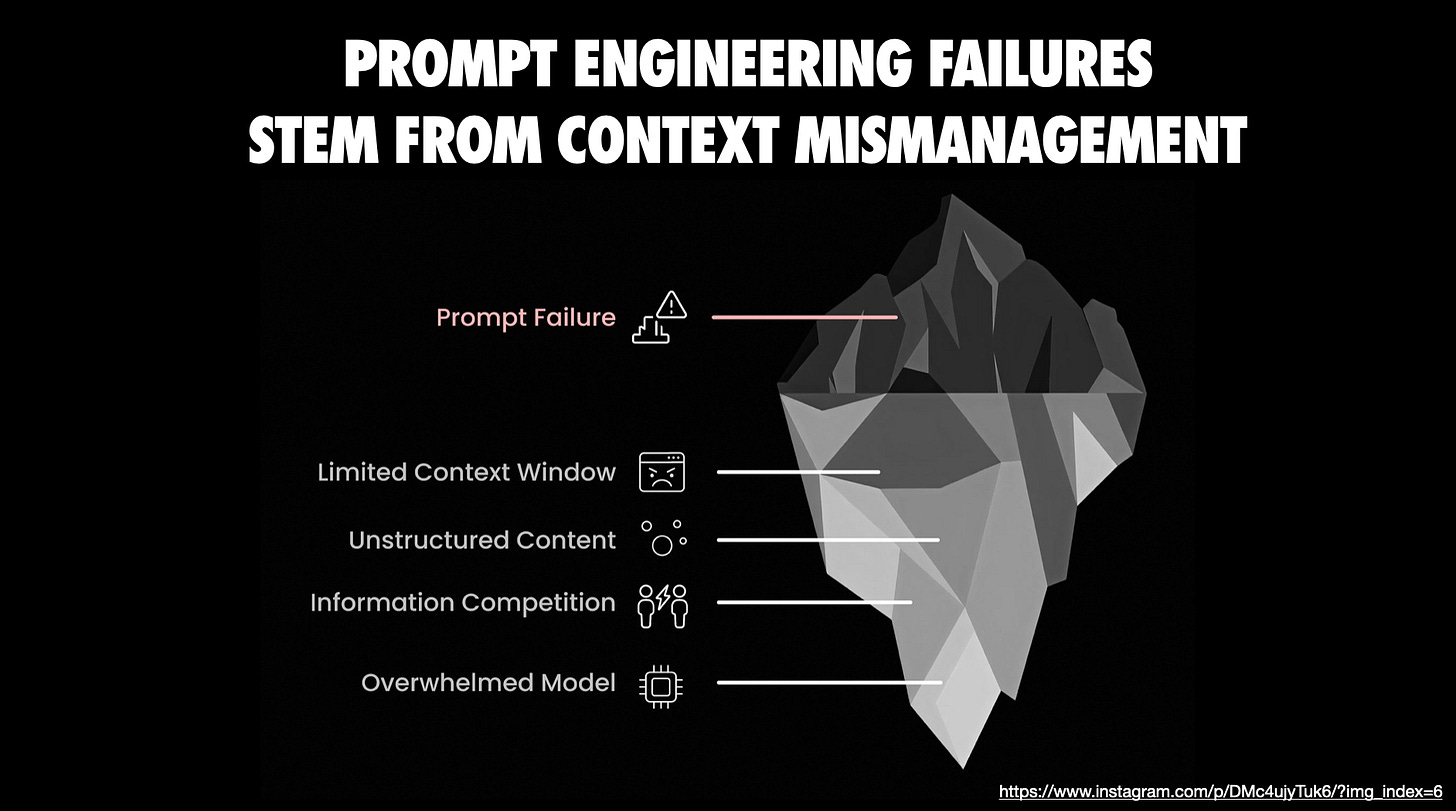

LLMs are only as good as the context you provide - show them the relevant code, docs, and constraints.

When working on a codebase, I make sure to feed the AI all the information it needs to perform well. That includes the code it should modify or refer to, the project’s technical constraints, and any known pitfalls or preferred approaches. Modern tools help with this: for example, Anthropic’s Claude can import an entire GitHub repo into its context in “Projects” mode, and IDE assistants like Cursor or Copilot auto-include open files in the prompt. But I often go further - I will either use an MCP like Context7 or manually copy important pieces of the codebase or API docs into the conversation if I suspect the model doesn’t have them.

Expert LLM users emphasize this “context packing” step. For example, doing a “brain dump” of everything the model should know before coding, including: high-level goals and invariants, examples of good solutions, and warnings about approaches to avoid. If I’m asking an AI to implement a tricky solution, I might tell it which naive solutions are too slow, or provide a reference implementation from elsewhere. If I’m using a niche library or a brand-new API, I’ll paste in the official docs or README so the AI isn’t flying blind. All of this upfront context dramatically improves the quality of its output, because the model isn’t guessing - it has the facts and constraints in front of it.

There are now utilities to automate context packaging. I’ve experimented with tools like gitingest or repo2txt, which essentially “dump” the relevant parts of your codebase into a text file for the LLM to read. These can be a lifesaver when dealing with a large project - you generate an output.txt bundle of key source files and let the model ingest that. The principle is: don’t make the AI operate on partial information. If a bug fix requires understanding four different modules, show it those four modules. Yes, we must watch token limits, but current frontier models have pretty huge context windows (tens of thousands of tokens). Use them wisely. I often selectively include just the portions of code relevant to the task at hand, and explicitly tell the AI what not to focus on if something is out of scope (to save tokens).

I think Claude Skills have potential because they turn what used to be fragile repeated prompting into something durable and reusable by packaging instructions, scripts, and domain specific expertise into modular capabilities that tools can automatically apply when a request matches the Skill. This means you get more reliable and context aware results than a generic prompt ever could and you move away from one off interactions toward workflows that encode repeatable procedures and team knowledge for tasks in a consistent way. A number of community-curated Skills collections exist, but one of my favorite examples is the frontend-design skill which can “end” the purple design aesthetic prevalent in LLM generated UIs. Until more tools support Skills officially, workarounds exist.

Finally, guide the AI with comments and rules inside the prompt. I might precede a code snippet with: “Here is the current implementation of X. We need to extend it to do Y, but be careful not to break Z.” These little hints go a long way. LLMs are literalists - they’ll follow instructions, so give them detailed, contextual instructions. By proactively providing context and guidance, we minimize hallucinations and off-base suggestions and get code that fits our project’s needs.

Choose the right model (and use multiple when needed)

Not all coding LLMs are equal - pick your tool with intention, and don’t be afraid to swap models mid-stream.

In 2025 we’ve been spoiled with a variety of capable code-focused LLMs. Part of my workflow is choosing the model or service best suited to each task. Sometimes it can be valuable to even try two or more LLMs in parallel to cross-check how they might approach the same problem differently.

Each model has its own “personality”. The key is: if one model gets stuck or gives mediocre outputs, try another. I’ve literally copied the same prompt from one chat into another service to see if it can handle it better. This “model musical chairs” can rescue you when you hit a model’s blind spot.

Also, make sure you’re using the best version available. If you can, use the newest “pro” tier models - because quality matters. And yes, it often means paying for access, but the productivity gains can justify it. Ultimately, pick the AI pair programmer whose “vibe” meshes with you. I know folks who prefer one model simply because they like how its responses feel. That’s valid - when you’re essentially in a constant dialogue with an AI, the UX and tone make a difference.

Personally I gravitate towards Gemini for a lot of coding work these days because the interaction feels more natural and it often understands my requests on the first try. But I will not hesitate to switch to another model if needed; sometimes a second opinion helps the solution emerge. In summary: use the best tool for the job, and remember you have an arsenal of AIs at your disposal.

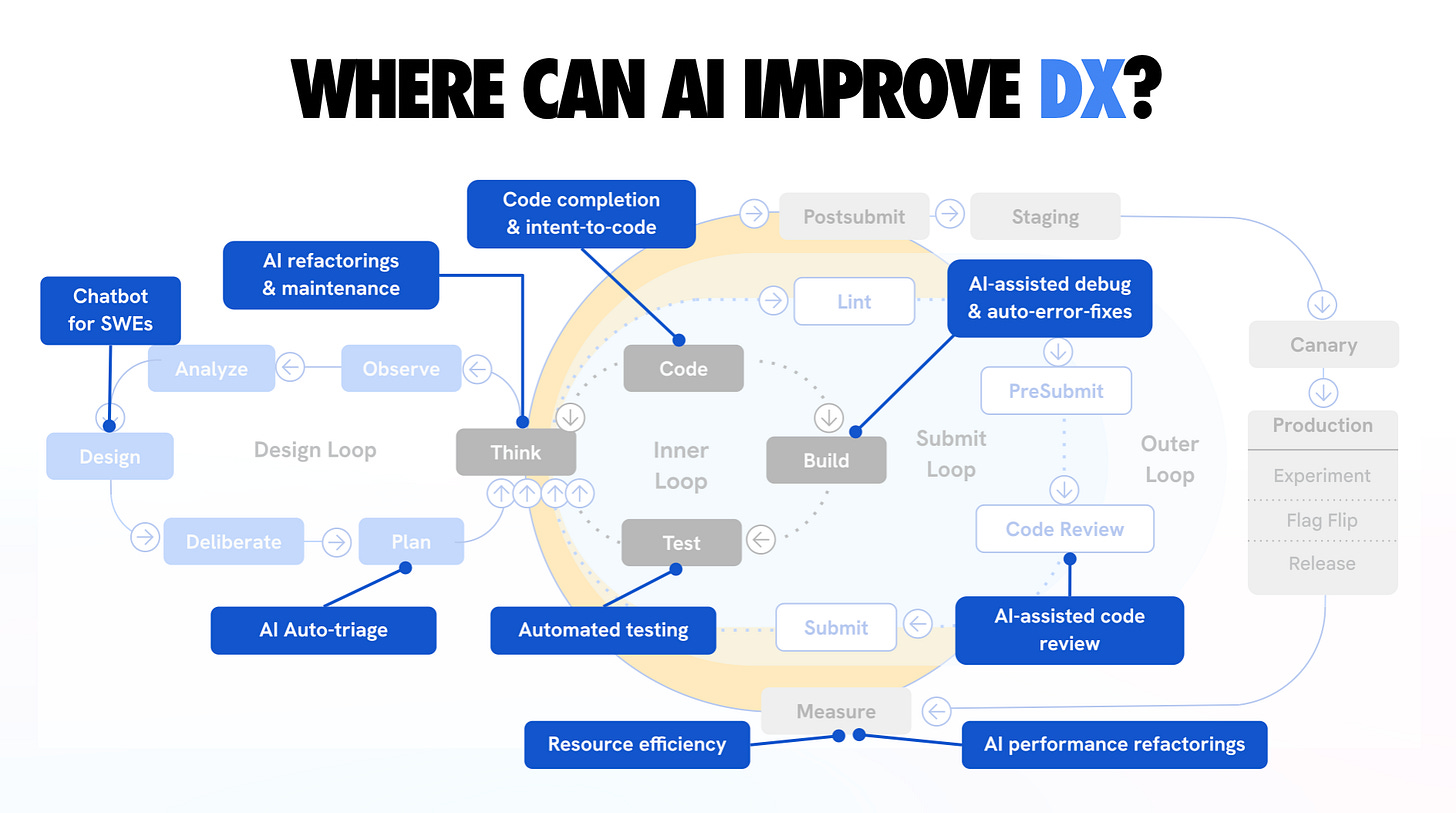

Leverage AI coding across the lifecycle

Supercharge your workflow with coding-specific AI help across the SDLC.

On the command-line, new AI agents emerged. Claude Code, OpenAI’s Codex CLI and Google’s Gemini CLI are CLI tools where you can chat with them directly in your project directory - they can read files, run tests, and even multi-step fix issues. I’ve used Google’s Jules and GitHub’s Copilot Agent as well - these are asynchronous coding agents that actually clone your repo into a cloud VM and work on tasks in the background (writing tests, fixing bugs, then opening a PR for you). It’s a bit eerie to witness: you issue a command like “refactor the payment module for X” and a little while later you get a pull request with code changes and passing tests. We are truly living in the future. You can read more about this in conductors to orchestrators.

That said, these tools are not infallible, and you must understand their limits. They accelerate the mechanical parts of coding - generating boilerplate, applying repetitive changes, running tests automatically - but they still benefit greatly from your guidance. For instance, when I use an agent like Claude or Copilot to implement something, I often supply it with the plan or to-do list from earlier steps so it knows the exact sequence of tasks. If the agent supports it, I’ll load up my spec.md or plan.md in the context before telling it to execute. This keeps it on track.

We’re not at the stage of letting an AI agent code an entire feature unattended and expecting perfect results. Instead, I use these tools in a supervised way: I’ll let them generate and even run code, but I keep an eye on each step, ready to step in when something looks off. There are also orchestration tools like Conductor that let you run multiple agents in parallel on different tasks (essentially a way to scale up AI help) - some engineers are experimenting with running 3-4 agents at once on separate features. I’ve dabbled in this “massively parallel” approach; it’s surprisingly effective at getting a lot done quickly, but it’s also mentally taxing to monitor multiple AI threads! For most cases, I stick to one main agent at a time and maybe a secondary one for reviews (discussed below).

Just remember these are power tools - you still control the trigger and guide the outcome.

A full overview of where AI can improve the developer experience. This spans design, inner, submit, and outer loops - highlighting every point where AI can meaningfully reduce toil.

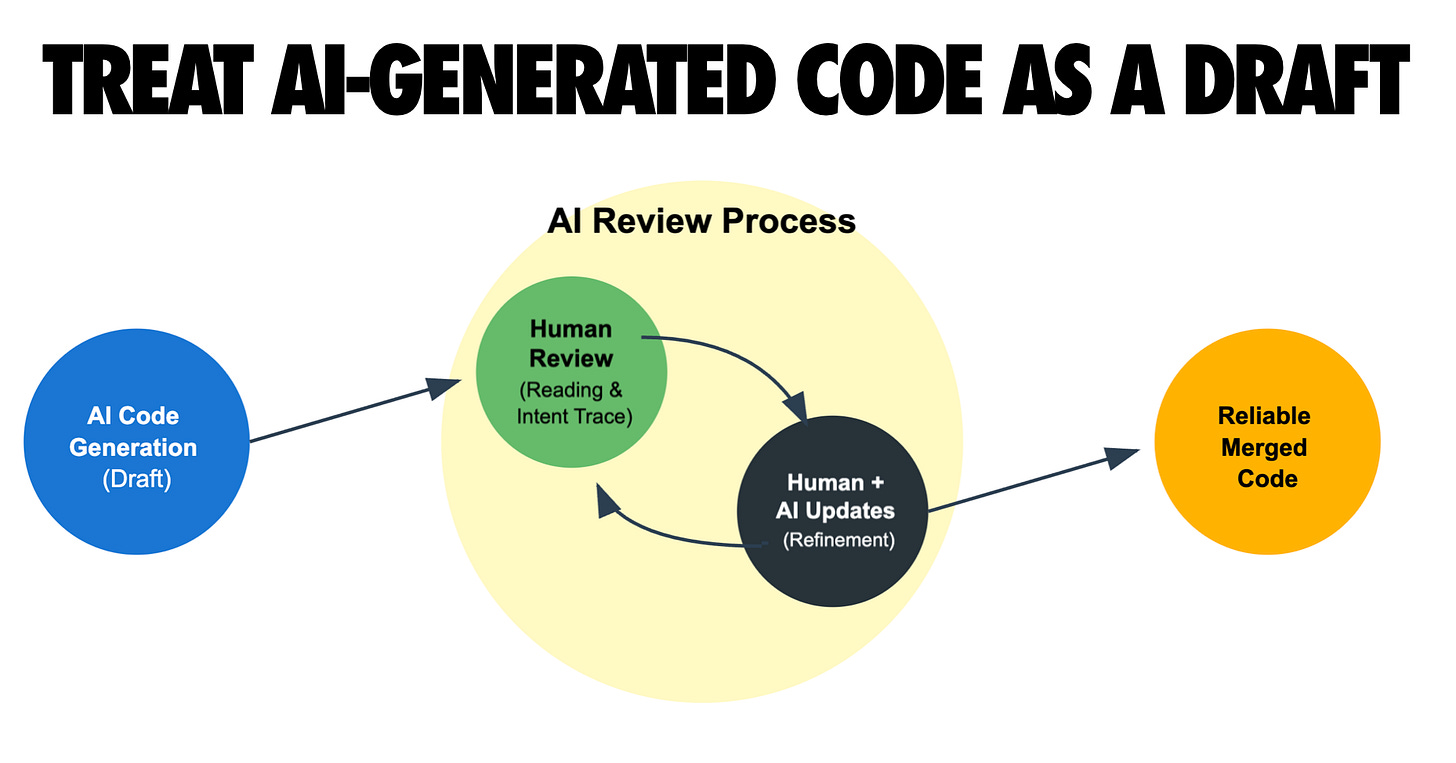

Keep a human in the loop - verify, test, and review everything

AI will happily produce plausible-looking code, but you are responsible for quality - always review and test thoroughly. One of my cardinal rules is never to blindly trust an LLM’s output. As Simon Willison aptly says, think of an LLM pair programmer as “over-confident and prone to mistakes”. It writes code with complete conviction - including bugs or nonsense - and won’t tell you something is wrong unless you catch it. So I treat every AI-generated snippet as if it came from a junior developer: I read through the code, run it, and test it as needed. You absolutely have to test what it writes - run those unit tests, or manually exercise the feature, to ensure it does what it claims. Read more about this in vibe coding is not an excuse for low-quality work.

In fact, I weave testing into the workflow itself. My earlier planning stage often includes generating a list of tests or a testing plan for each step. If I’m using a tool like Claude Code, I’ll instruct it to run the test suite after implementing a task, and have it debug failures if any occur. This kind of tight feedback loop (write code → run tests → fix) is something AI excels at as long as the tests exist. It’s no surprise that those who get the most out of coding agents tend to be those with strong testing practices. An agent like Claude can “fly” through a project with a good test suite as safety net. Without tests, the agent might blithely assume everything is fine (“sure, all good!”) when in reality it’s broken several things. So, invest in tests - it amplifies the AI’s usefulness and confidence in the result.

Even beyond automated tests, do code reviews - both manual and AI-assisted. I routinely pause and review the code that’s been generated so far, line by line. Sometimes I’ll spawn a second AI session (or a different model) and ask it to critique or review code produced by the first. For example, I might have Claude write the code and then ask Gemini, “Can you review this function for any errors or improvements?” This can catch subtle issues. The key is to not skip the review just because an AI wrote the code. If anything, AI-written code needs extra scrutiny, because it can sometimes be superficially convincing while hiding flaws that a human might not immediately notice.

I also use Chrome DevTools MCP, built with my last team, for my debugging and quality loop to bridge the gap between static code analysis and live browser execution. It “gives your agent eyes”. It lets me grant my AI tools direct access to see what the browser can, inspect the DOM, get rich performance traces, console logs or network traces. This integration eliminates the friction of manual context switching, allowing for automated UI testing directly through the LLM. It means bugs can be diagnosed and fixed with high precision based on actual runtime data.

The dire consequences of skipping human oversight have been documented. One developer who leaned heavily on AI generation for a rush project described the result as an inconsistent mess - duplicate logic, mismatched method names, no coherent architecture. He realized he’d been “building, building, building” without stepping back to really see what the AI had woven together. The fix was a painful refactor and a vow to never let things get that far out of hand again. I’ve taken that to heart. No matter how much AI I use, I remain the accountable engineer.

In practical terms, that means I only merge or ship code after I’ve understood it. If the AI generates something convoluted, I’ll ask it to add comments explaining it, or I’ll rewrite it in simpler terms. If something doesn’t feel right, I dig in - just as I would if a human colleague contributed code that raised red flags.

It’s all about mindset: the LLM is an assistant, not an autonomously reliable coder. I am the senior dev; the LLM is there to accelerate me, not replace my judgment. Maintaining this stance not only results in better code, it also protects your own growth as a developer. (I’ve heard some express concern that relying too much on AI might dull their skills - I think as long as you stay in the loop, actively reviewing and understanding everything, you’re still sharpening your instincts, just at a higher velocity.) In short: stay alert, test often, review always. It’s still your codebase at the end of the day.

Commit often and use version control as a safety net. Never commit code you can’t explain.

Frequent commits are your save points - they let you undo AI missteps and understand changes.

When working with an AI that can generate a lot of code quickly, it’s easy for things to veer off course. I mitigate this by adopting ultra-granular version control habits. I commit early and often, even more than I would in normal hand-coding. After each small task or each successful automated edit, I’ll make a git commit with a clear message. This way, if the AI’s next suggestion introduces a bug or a messy change, I have a recent checkpoint to revert to (or cherry-pick from) without losing hours of work. One practitioner likened it to treating commits as “save points in a game” - if an LLM session goes sideways, you can always roll back to the last stable commit. I’ve found that advice incredibly useful. It’s much less stressful to experiment with a bold AI refactor when you know you can undo it with a git reset if needed.

Proper version control also helps when collaborating with the AI. Since I can’t rely on the AI to remember everything it’s done (context window limitations, etc.), the git history becomes a valuable log. I often scan my recent commits to brief the AI (or myself) on what changed. In fact, LLMs themselves can leverage your commit history if you provide it - I’ve pasted git diffs or commit logs into the prompt so the AI knows what code is new or what the previous state was. Amusingly, LLMs are really good at parsing diffs and using tools like git bisect to find where a bug was introduced. They have infinite patience to traverse commit histories, which can augment your debugging. But this only works if you have a tidy commit history to begin with.

Another benefit: small commits with good messages essentially document the development process, which helps when doing code review (AI or human). If an AI agent made five changes in one go and something broke, having those changes in separate commits makes it easier to pinpoint which commit caused the issue. If everything is in one giant commit titled “AI changes”, good luck! So I discipline myself: finish task, run tests, commit. This also meshes well with the earlier tip about breaking work into small chunks - each chunk ends up as its own commit or PR.

Finally, don’t be afraid to use branches or worktrees to isolate AI experiments. One advanced workflow I’ve adopted (inspired by folks like Jesse Vincent) is to spin up a fresh git worktree for a new feature or sub-project. This lets me run multiple AI coding sessions in parallel on the same repo without them interfering, and I can later merge the changes. It’s a bit like having each AI task in its own sandbox branch. If one experiment fails, I throw away that worktree and nothing is lost in main. If it succeeds, I merge it in. This approach has been crucial when I’m, say, letting an AI implement Feature A while I (or another AI) work on Feature B simultaneously. Version control is what makes this coordination possible. In short: commit often, organize your work with branches, and embrace git as the control mechanism to keep AI-generated changes manageable and reversible.

Customize the AI’s behavior with rules and examples

Steer your AI assistant by providing style guides, examples, and even “rules files” - a little upfront tuning yields much better outputs.

One thing I learned is that you don’t have to accept the AI’s default style or approach - you can influence it heavily by giving it guidelines. For instance, I have a CLAUDE.md file that I update periodically, which contains process rules and preferences for Claude (Anthropic’s model) to follow (and similarly a GEMINI.md when using Gemini CLI). This includes things like “write code in our project’s style, follow our lint rules, don’t use certain functions, prefer functional style over OOP,” etc. When I start a session, I feed this file to Claude to align it with our conventions. It’s surprising how well this works to keep the model “on track” as Jesse Vincent noted - it reduces the tendency of the AI to go off-script or introduce patterns we don’t want.

Even without a fancy rules file, you can set the tone with custom instructions or system prompts. GitHub Copilot and Cursor both introduced features to let you configure the AI’s behavior globally for your project. I’ve taken advantage of that by writing a short paragraph about our coding style, e.g. “Use 4 spaces indent, avoid arrow functions in React, prefer descriptive variable names, code should pass ESLint.” With those instructions in place, the AI’s suggestions adhere much more closely to what a human teammate might write. Ben Congdon mentioned how shocked he was that few people use Copilot’s custom instructions, given how effective they are - he could guide the AI to output code matching his team’s idioms by providing some examples and preferences upfront. I echo that: take the time to teach the AI your expectations.

Another powerful technique is providing in-line examples of the output format or approach you want. If I want the AI to write a function in a very specific way, I might first show it a similar function already in the codebase: “Here’s how we implemented X, use a similar approach for Y.” If I want a certain commenting style, I might write a comment myself and ask the AI to continue in that style. Essentially, prime the model with the pattern to follow. LLMs are great at mimicry - show them one or two examples and they’ll continue in that vein.

The community has also come up with creative “rulesets” to tame LLM behavior. You might have heard of the “Big Daddy” rule or adding a “no hallucination/no deception” clause to prompts. These are basically tricks to remind the AI to be truthful and not overly fabricate code that doesn’t exist. For example, I sometimes prepend a prompt with: “If you are unsure about something or the codebase context is missing, ask for clarification rather than making up an answer.” This reduces hallucinations. Another rule I use is: “Always explain your reasoning briefly in comments when fixing a bug.” This way, when the AI generates a fix, it will also leave a comment like “// Fixed: Changed X to Y to prevent Z (as per spec).” That’s super useful for later review.

In summary, don’t treat the AI as a black box - tune it. By configuring system instructions, sharing project docs, or writing down explicit rules, you turn the AI into a more specialized developer on your team. It’s akin to onboarding a new hire: you’d give them the style guide and some starter tips, right? Do the same for your AI pair programmer. The return on investment is huge: you get outputs that need less tweaking and integrate more smoothly with your codebase.

Embrace testing and automation as force multipliers

Use your CI/CD, linters, and code review bots - AI will work best in an environment that catches mistakes automatically.

This is a corollary to staying in the loop and providing context: a well-oiled development pipeline enhances AI productivity. I ensure that any repository where I use heavy AI coding has a robust continuous integration setup. That means automated tests run on every commit or PR, code style checks (like ESLint, Prettier, etc.) are enforced, and ideally a staging deployment is available for any new branch. Why? Because I can let the AI trigger these and evaluate the results. For instance, if the AI opens a pull request via a tool like Jules or GitHub Copilot Agent, our CI will run tests and report failures. I can feed those failure logs back to the AI: “The integration tests failed with XYZ, let’s debug this.” It turns bug-fixing into a collaborative loop with quick feedback, which AIs handle quite well (they’ll suggest a fix, we run CI again, and iterate).

Automated code quality checks (linters, type checkers) also guide the AI. I actually include linter output in the prompt sometimes. If the AI writes code that doesn’t pass our linter, I’ll copy the linter errors into the chat and say “please address these issues.” The model then knows exactly what to do. It’s like having a strict teacher looking over the AI’s shoulder. In my experience, once the AI is aware of a tool’s output (like a failing test or a lint warning), it will try very hard to correct it - after all, it “wants” to produce the right answer. This ties back to providing context: give the AI the results of its actions in the environment (test failures, etc.) and it will learn from them.

AI coding agents themselves are increasingly incorporating automation hooks. Some agents will refuse to say a code task is “done” until all tests pass, which is exactly the diligence you want. Code review bots (AI or otherwise) act as another filter - I treat their feedback as additional prompts for improvement. For example, if CodeRabbit or another reviewer comments “This function is doing X which is not ideal” I will ask the AI, “Can you refactor based on this feedback?”

By combining AI with automation, you start to get a virtuous cycle. The AI writes code, the automated tools catch issues, the AI fixes them, and so forth, with you overseeing the high-level direction. It feels like having an extremely fast junior dev whose work is instantly checked by a tireless QA engineer. But remember, you set up that environment. If your project lacks tests or any automated checks, the AI’s work may slip through with subtle bugs or poor quality until much later.

So as we head into 2026, one of my goals is to bolster the quality gates around AI code contribution: more tests, more monitoring, perhaps even AI-on-AI code reviews. It might sound paradoxical (AIs reviewing AIs), but I’ve seen it catch things one model missed. Bottom line: an AI-friendly workflow is one with strong automation - use those tools to keep the AI honest.

Continuously learn and adapt (AI amplifies your skills)

Treat every AI coding session as a learning opportunity - the more you know, the more the AI can help you, creating a virtuous cycle.

One of the most exciting aspects of using LLMs in development is how much I have learned in the process. Rather than replacing my need to know things, AIs have actually exposed me to new languages, frameworks, and techniques I might not have tried on my own.

This pattern holds generally: if you come to the table with solid software engineering fundamentals, the AI will amplify your productivity multifold. If you lack that foundation, the AI might just amplify confusion. Seasoned devs have observed that LLMs “reward existing best practices” - things like writing clear specs, having good tests, doing code reviews, etc., all become even more powerful when an AI is involved. In my experience, the AI lets me operate at a higher level of abstraction (focusing on design, interface, architecture) while it churns out the boilerplate, but I need to have those high-level skills first. As Simon Willison notes, almost everything that makes someone a senior engineer (designing systems, managing complexity, knowing what to automate vs hand-code) is what now yields the best outcomes with AI. So using AIs has actually pushed me to up my engineering game - I’m more rigorous about planning and more conscious of architecture, because I’m effectively “managing” a very fast but somewhat naïve coder (the AI).

For those worried that using AI might degrade their abilities: I’d argue the opposite, if done right. By reviewing AI code, I’ve been exposed to new idioms and solutions. By debugging AI mistakes, I’ve deepened my understanding of the language and problem domain. I often ask the AI to explain its code or the rationale behind a fix - kind of like constantly interviewing a candidate about their code - and I pick up insights from its answers. I also use AI as a research assistant: if I’m not sure about a library or approach, I’ll ask it to enumerate options or compare trade-offs. It’s like having an encyclopedic mentor on call. All of this has made me a more knowledgeable programmer.

The big picture is that AI tools amplify your expertise. Going into 2026, I’m not afraid of them “taking my job” - I’m excited that they free me from drudgery and allow me to spend more time on creative and complex aspects of software engineering. But I’m also aware that for those without a solid base, AI can lead to Dunning-Kruger on steroids (it may seem like you built something great, until it falls apart). So my advice: continue honing your craft, and use the AI to accelerate that process. Be intentional about periodically coding without AI too, to keep your raw skills sharp. In the end, the developer + AI duo is far more powerful than either alone, and the developer half of that duo has to hold up their end.

Conclusion

As we enter 2026, I’ve fully embraced AI in my development workflow - but in a considered, expert-driven way. My approach is essentially “AI-augmented software engineering” rather than AI-automated software engineering.

I’ve learned: the best results come when you apply classic software engineering discipline to your AI collaborations. It turns out all our hard-earned practices - design before coding, write tests, use version control, maintain standards - not only still apply, but are even more important when an AI is writing half your code.

I’m excited for what’s next. The tools keep improving and my workflow will surely evolve alongside them. Perhaps fully autonomous “AI dev interns” will tackle more grunt work while we focus on higher-level tasks. Perhaps new paradigms of debugging and code exploration will emerge. No matter what, I plan to stay in the loop - guiding the AIs, learning from them, and amplifying my productivity responsibly.

The bottom line for me: AI coding assistants are incredible force multipliers, but the human engineer remains the director of the show.

With that…happy building in 2026! 🚀

I’m excited to share I’ve released a new AI-assisted engineering book with O’Reilly. There are a number of free tips on the book site in case interested.

Thank you for sharing!

Can’t believe this is free! My new year’s resolution should look like this.